A conversation between Hallie Ringle, Assistant Curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and Martin Eisenberg

HR: Can you tell me a little bit about how you came to this particular grouping of artists? Did something formally about each of the works speak to you or are there specific conversations happening between the works that you found to be interesting?

ME: Most of the artists chosen were either a part of the artists in residence program at the Studio Museum in Harlem or exhibited at the museum during my association with the museum as part of the acquisition committee. This exhibition is a tribute to the Studio Museum’s program and its long reaching effect. As far as the works speaking to one another, because they all come from my personal collection there is a connecting thread running through all of them. I feel that I can grab any work and somehow it will fit alongside another one perfectly. At the time of this conversation we haven’t yet installed the show so a lot remains to be seen. Hopefully it won’t be a mess. But let’s be honest, so many of these artists are friends and admirers of each other and have been shown together in a variety of shows. All are of African descent. This show can’t miss…the connections are so strong.

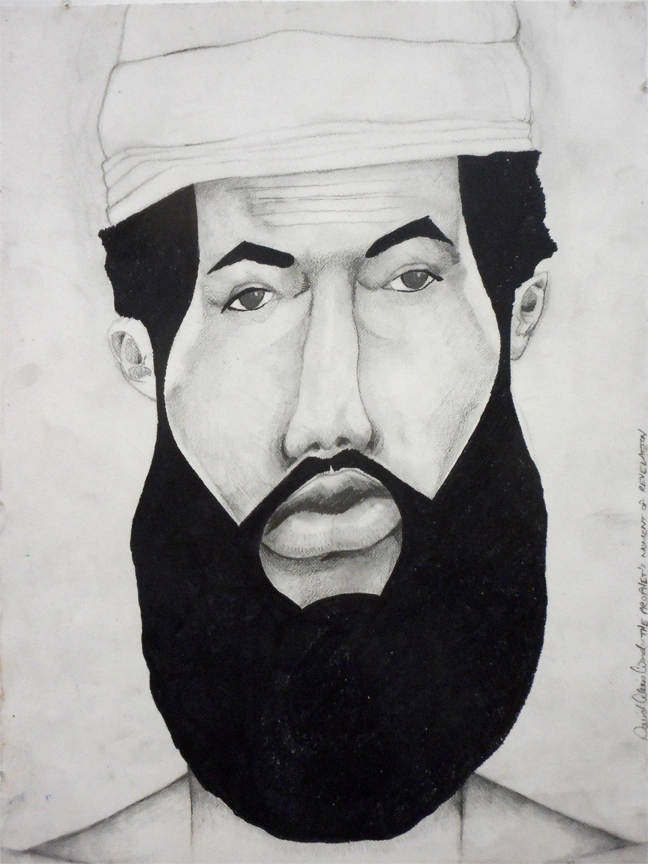

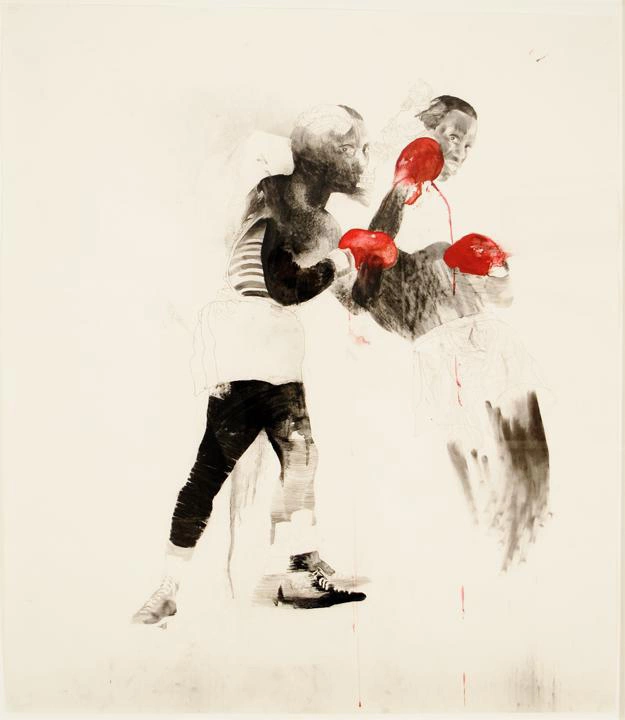

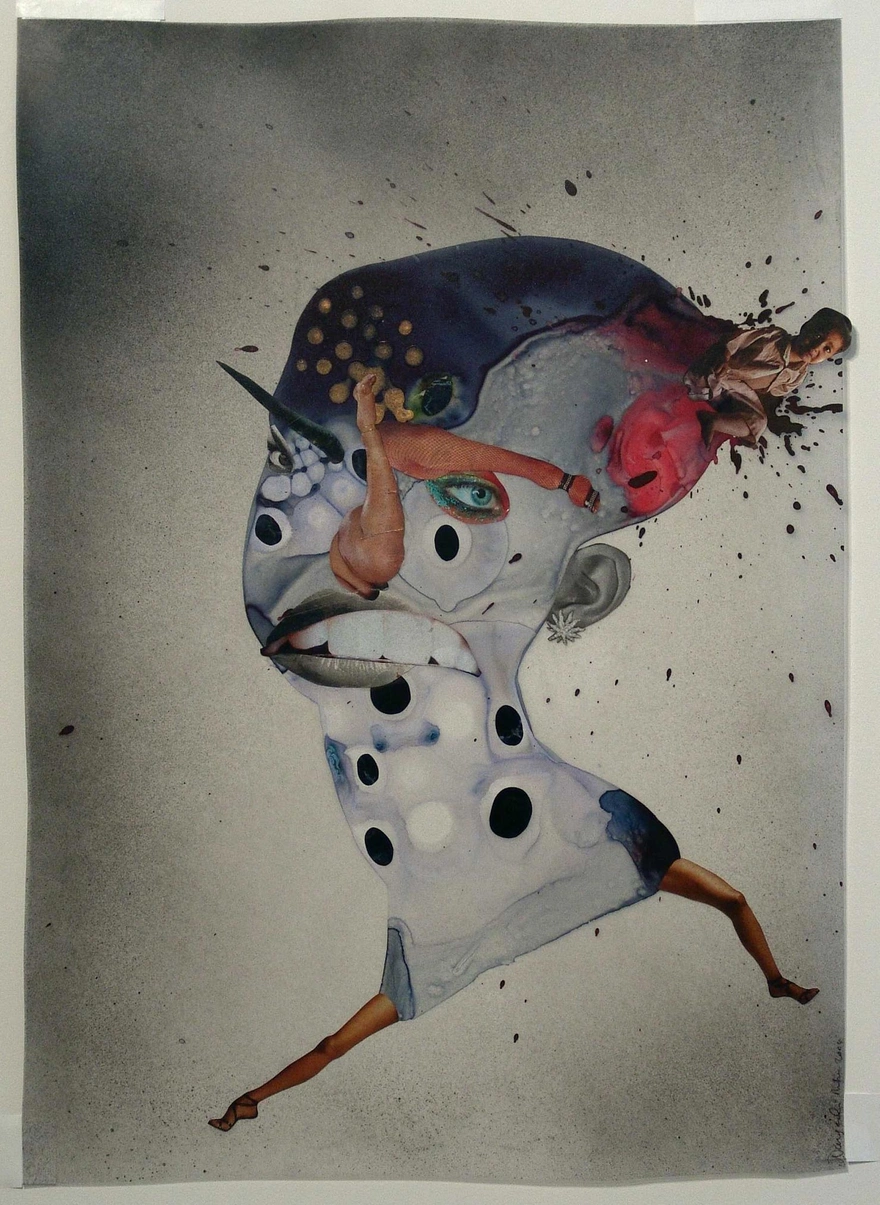

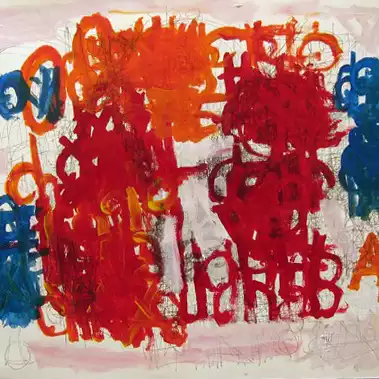

HR: So true! I love that there’s such a mix of figuration and abstraction on your checklist. It seems increasingly important to show multiple ways of working, particularly for artists of color, since figurative works seem to be dominating the art world lately. How did you balance the figurative, the abstract, and the conceptual on this checklist? Do you seek a balance within your own collection?

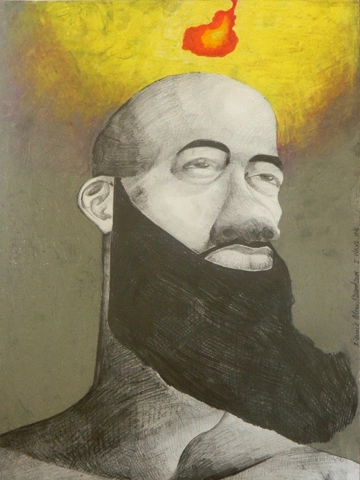

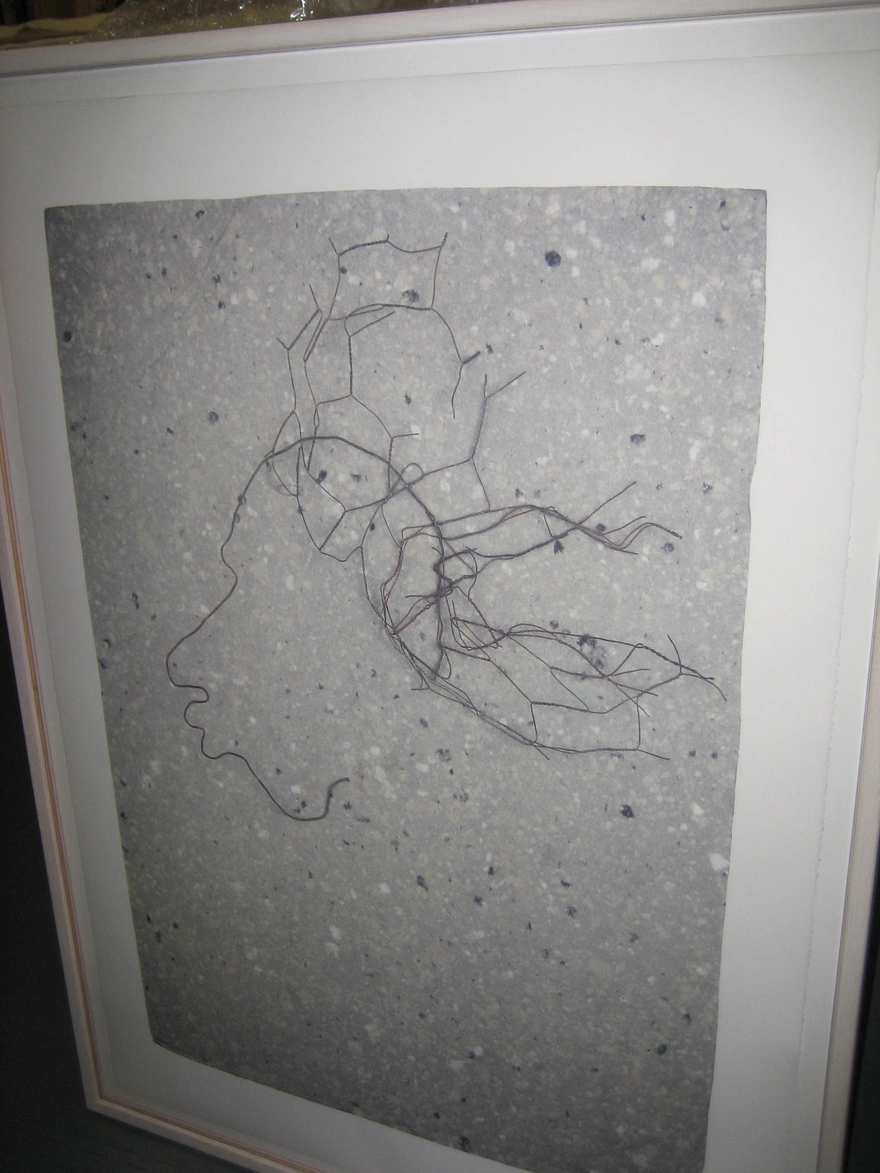

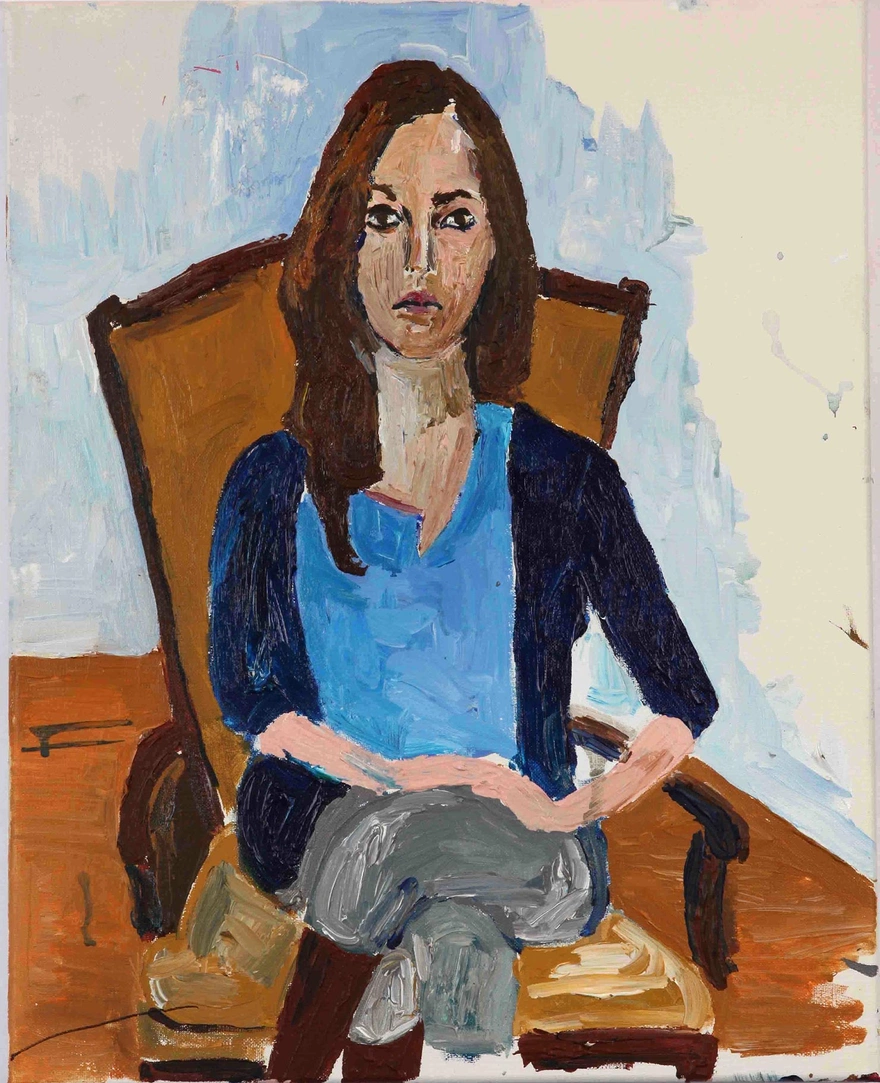

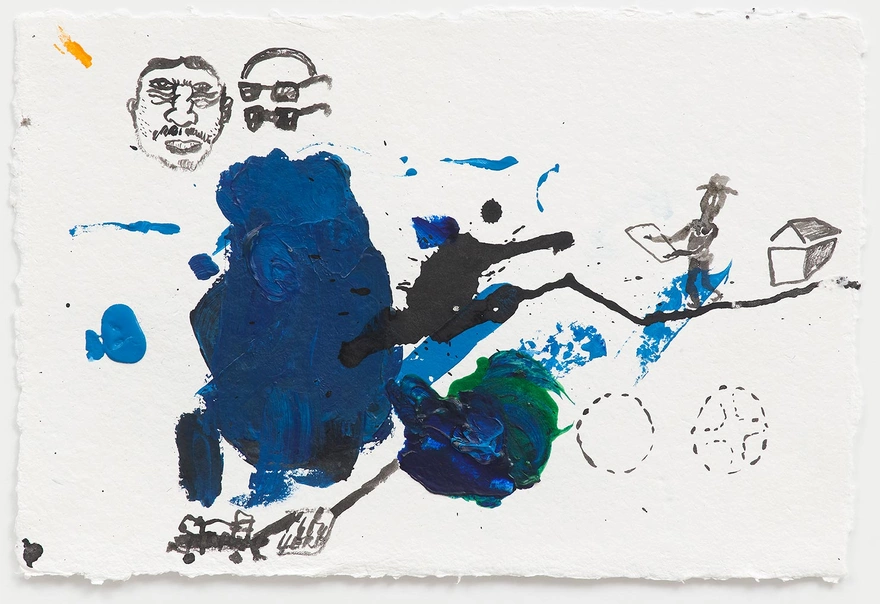

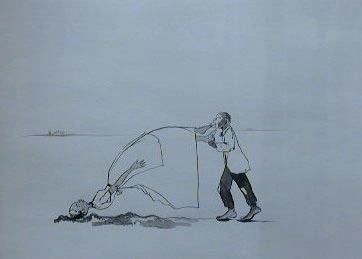

ME: I really don’t think too much about working styles. I’m a very impulsive buyer and seeker. I do have a thing for expressionistic approaches. Henry Taylor, Gary Simmons, Walter Price, and Jack Whitten all work in different styles but all are very expressionistic. I also love handmade objects and value understatement. David Hammons, Kara Walker, and Dave McKenzie each fall into that category but have entirely different practices. I love variety and have built a collection that hopefully is unpredictable and surprising. At the Studio Museum’s acquisition meetings all of us appreciate the wide scope of work that is presented to us by curators like you: photography, drawing, painting, video, and performance based. My personal collection reflects the same values and scope.

HR: I think that’s such an interesting way to think about building a collection and so it makes a lot of sense that it’s so cohesive. Many artists in your show have been profoundly influenced by Harlem. What do you think it is about Harlem that provides this kind of creative fodder? How has Harlem influenced you as a collector?

ME: It seems as if Harlem has had a major effect throughout the world ever since the Harlem Renaissance. Writers, artists, and musicians have spoken about Harlem’s history and its effect on world culture for as long as I can remember. I was taken up to Harlem around 20 years ago by the art dealer Jack Tilton to visit the studio of the artist Nari Ward. I was enthralled by the energy and the colorful street scenes. We started going up there on a regular basis and those visits included stops at the Studio Museum. I have a long history with the jazz world, so collecting African American art was a natural move. Tilton was an expert and he introduced me to many artists including David Hammons. Hammons and I shared a love of jazz and we got along well. He is a cornerstone of the collection. In the end it’s the people that you meet that have the largest effect on your thinking and the direction that your life will take. People like Jack, Thelma Golden, A C Hudgins, and Lowery Stokes Sims all played major roles in my development as an arts patron. That’s how Harlem has become a central part of my life. You are a curator and are more educated than I am regarding Harlem’s history and its influence on the arts. I’d like to hear your thoughts and how working in Harlem has changed your life.

HR: Harlem has been incredibly influential to me as a curator; there’s something about getting off the subway at 125th (or any subway stop in Harlem) that immediately locates you in the neighborhood. As you pointed out, the vibrant energy is completely unique to Harlem and I can’t think of another NYC neighborhood with such a distinct identity. It’s one of the only places where I see vendors on the street selling goods like tiny Hammons flags and oils. I’m originally from North Carolina and the spirit of Harlem reminds me a lot of the town I’m from—there people sit on porches and here people sit on stoops but in both communities people go out of their way to acknowledge each other, something that doesn’t happen in this city often. I love how artistic and creative moments are always happening in Harlem; walking around Harlem I never know if I’m going to see a marching band or drums or a new mural. I love that people experience art constantly so it becomes an expectation of the norm rather than an event that you have to mark your calendar to see. At the Museum, it’s been incredibly influential to my curatorial practice. I, and the other curators, are constantly asking ourselves how to reflect this in the galleries. Harlem has an incredible artistic legacy, one that’s most famous for the Harlem Renaissance but, in reality, it’s still a major hub for cultural production. Now that the Museum is in its inHarlem phase, the local community is more important than ever. Doing exhibitions at places like Countee Cullen, the Schomburg, and Marcus Garvey Park, I’ve come in contact with people that, for me, form the heart of Harlem. I know you mentioned that you get along with David Hammons quite well, and I noticed that most of the artists on the Uptown to Harlem checklist have several works representing their practice. Do your relationships with artists inform your collection and did they inform this exhibition?

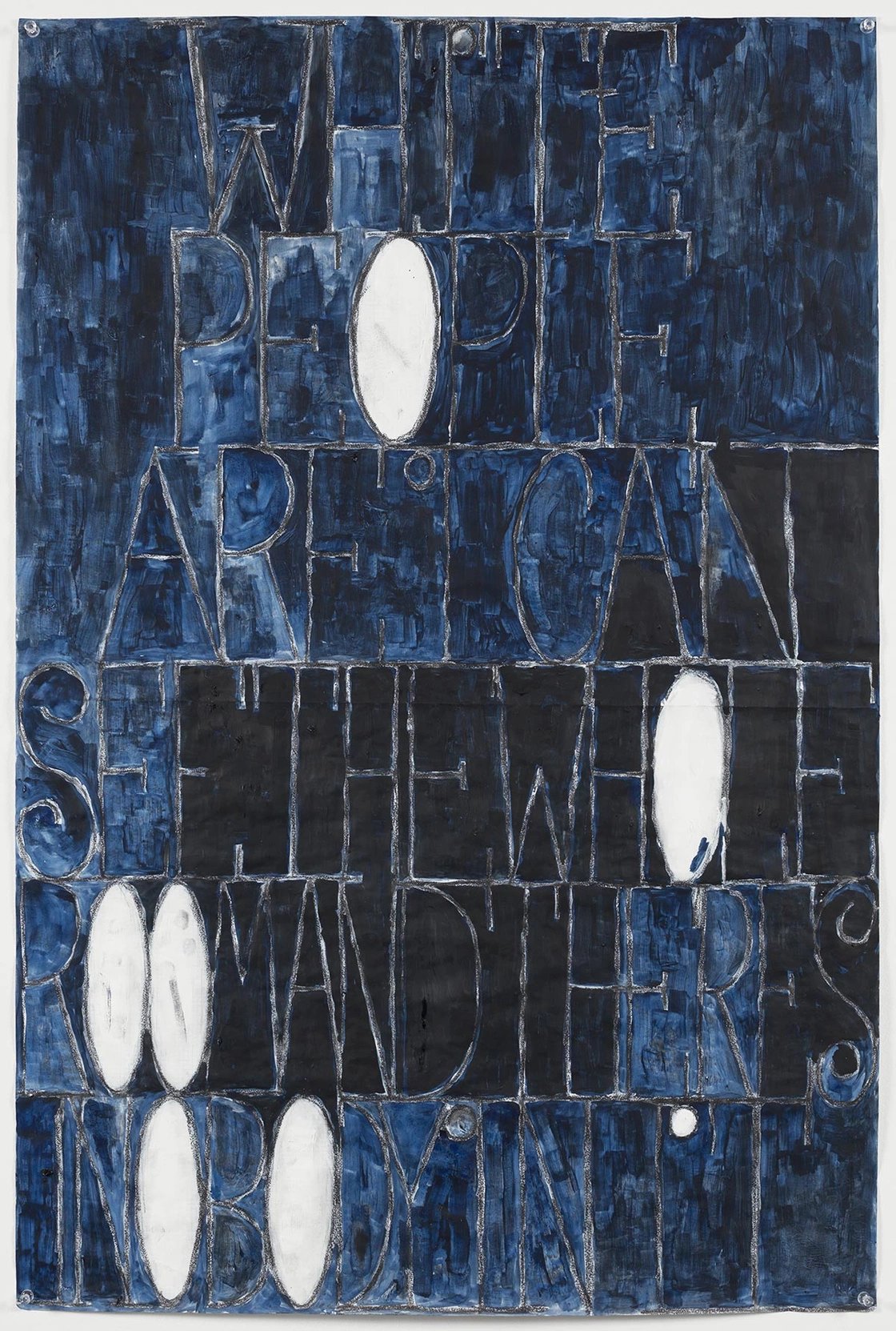

ME: I don’t want to overstate my relationship with Hammons. David is a very private person and difficult to get close to. That being said we’ve had a nice working relationship, which is what I strive for with artists we collect. Those relationships do not come into play when planning exhibitions. Truthfully these exhibitions are thought of and produced with lightning speed. It’s a quick intuitive idea that pops up and then I contact Emily, who manages the collection, and we discuss what works we think fit in. We play by certain rules: most works are under glass and we avoid nudity, crass imagery, and obscene language. The shows are geared toward the student population and we’re careful not to offend. We hope to put on shows that challenge people’s thoughts and perceptions about contemporary art. In the case of this particular show I assume that many people are unfamiliar with art made by African Americans. After all, up until very recently it was hard to find examples in most museum collections or in exhibitions being mounted across the country. Many of the people walking through our gallery rarely go out to view art. Rebeca and I see this as an opportunity and enjoy knowing that our small gallery can enlighten and educate at a glance.

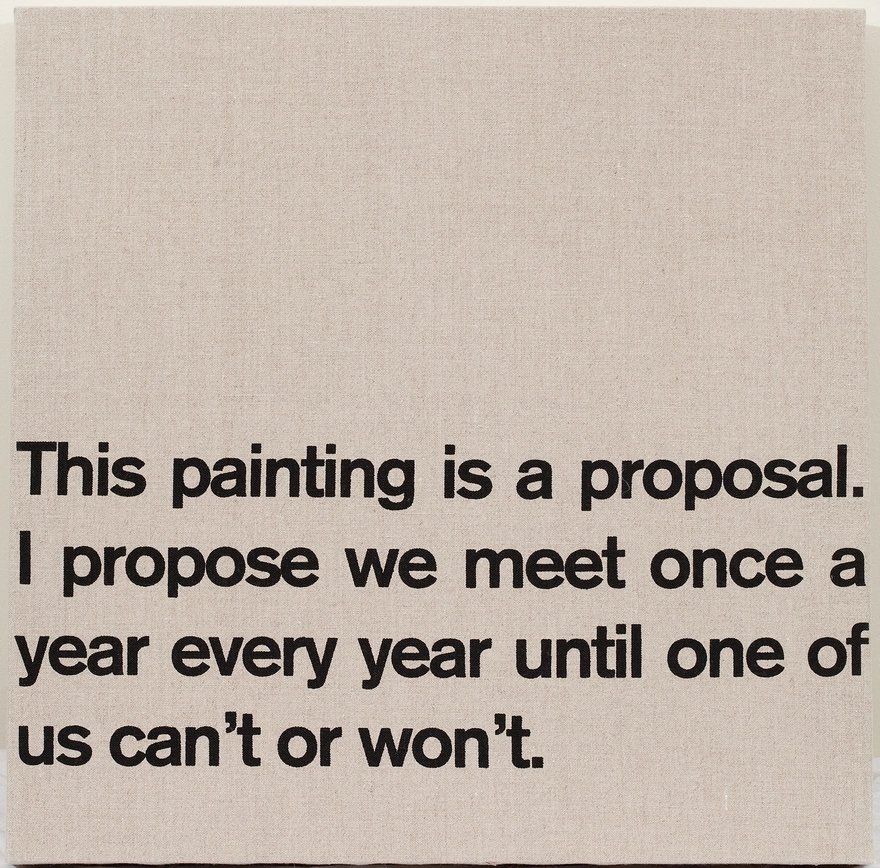

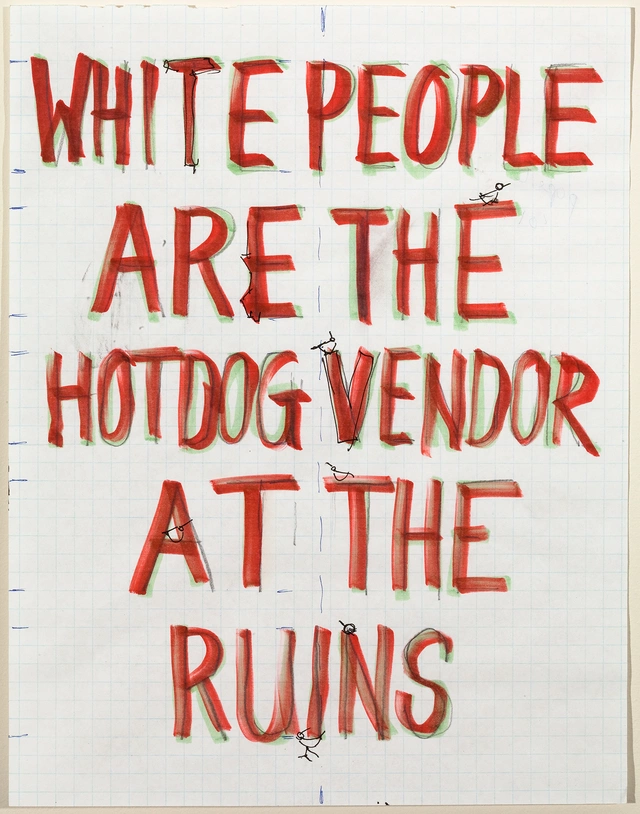

HR: I think your approach is exactly right—trust your audience. I read all of our comments from our Reading and Reflection room here at the Museum and I find that most people find meaning in even the most opaque work. Personally, I’m especially into the Pope.L hotdog vendor work. By placing this work at Riverview, what conversations are you hoping to achieve / are you most excited about? What work are you most excited to share?

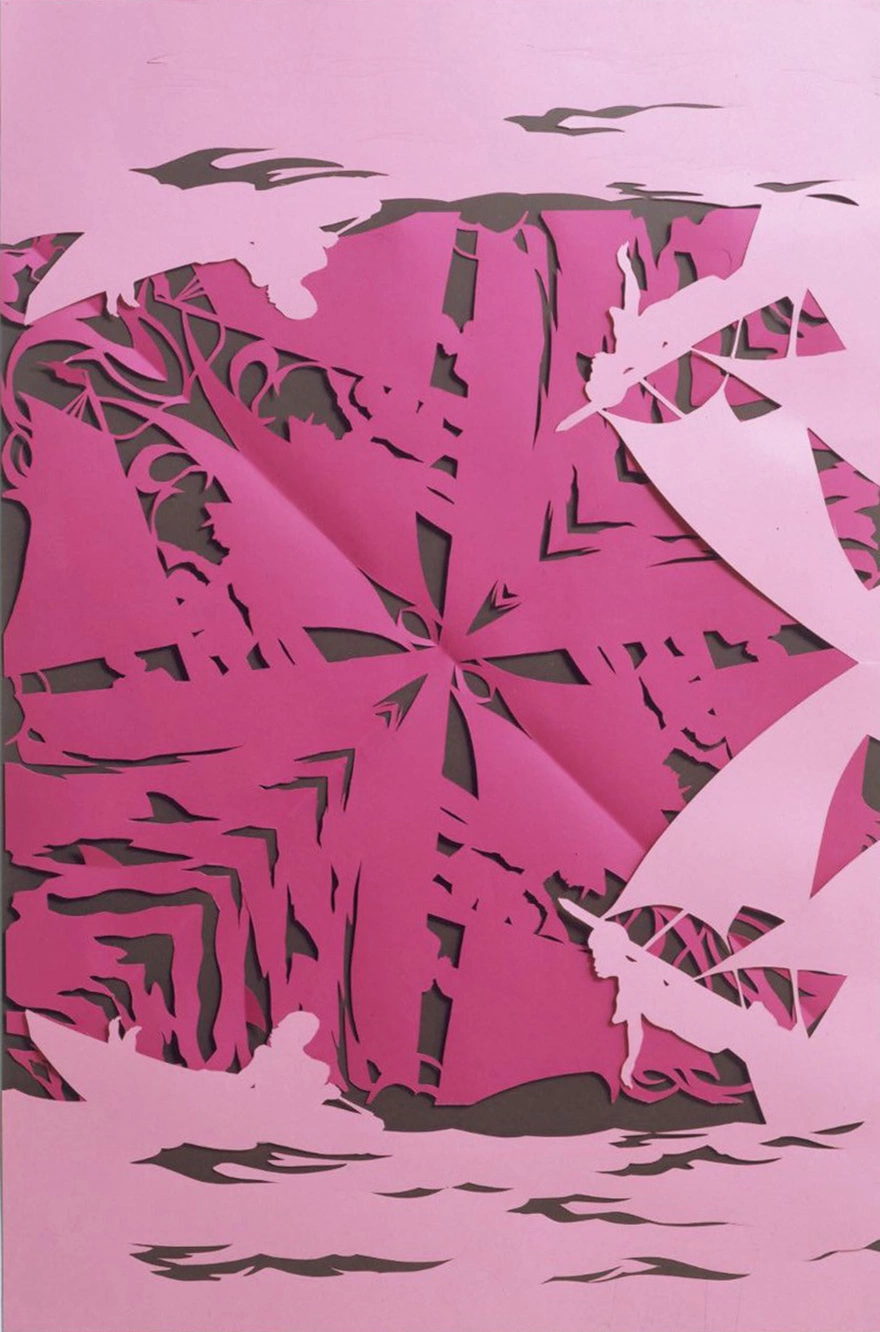

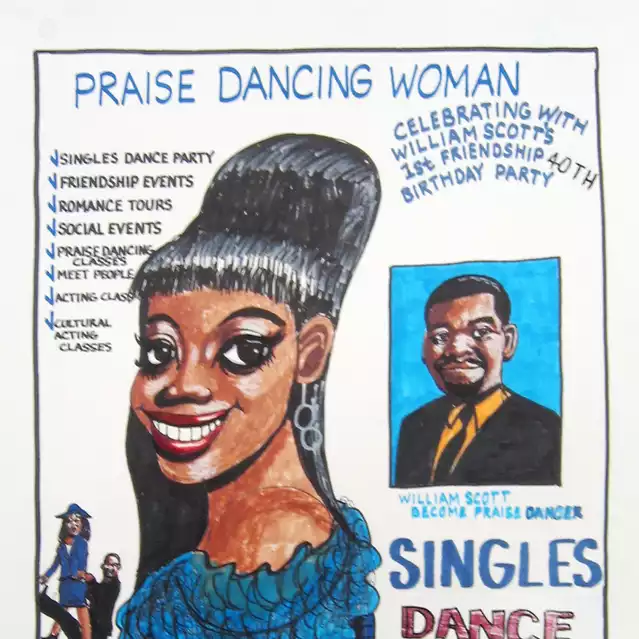

ME: You’re right to have picked the Pope.L out of the checklist. The kids always gravitate toward works with text. In the last exhibit we had a David Shrigley piece with the words “It’s a Dream/ It’s Not a Dream.” They went crazy over it, wondering what it meant. The hot dog vendor text should spin some heads, as well as Dave McKenzie’s text painting. I’m excited about Walter Price who both of us admire. His child like approach should resonate. The Nari Ward sculpture is a high profile piece for the gallery. We rarely show sculptural works because of the limited space and fear of damage. This piece is tough enough and is comical like much of Nari’s best work. The Kara Walker is also a highlight. It’s a chance for the school population to live with a great example by a major artist of historic importance.

HR: I also appreciate Walter’s use of color, which struck so many people coming into the galleries during Fictions. Thank you for recommending him! This is more of an observation than a question but, even in my time at Studio your gifts to the Museum have played an incredibly important role in the development of the collection. The work you bring in to Studio Museum by artists like Walter Price or William Scott are, in many cases, people that we haven’t heard of before but become singularly important artists that many major institutions end up collecting. Your work helps to ensure the preservation of the artist’s work and the Museum’s reputation for visionary collecting practices. Do you think about this when you’re collecting work? How did you approach curating this exhibition differently than selecting the work you live with in your home?

ME: We mostly buy the work of young and up and coming artists. Many times we buy from their first show. We hope that the work becomes valued and is looked upon as being important down the road and we enjoy placing works in museum collections. That being said, while we take advice from curators and gallerists we buy impulsively and with our hearts. Most of what we buy will be forgotten by the masses and unwanted by major museums. That’s the reality, which is why it’s important to us to support galleries and artists that are making a cultural difference and have a distinct point of view. There is not much of a difference between what we hang in our home and what you see in a Riverview show. Every show we hang is a part of who we are. That’s a good way to end the conversation. Thanks Hallie.