Text from curator Kelly Taxter

Night was dark, but the sky was blue,

Down the alley, the ice wagon flew,

Heard a bump, and somebody screamed,

You should’ve heard just what I seen.

You Should’ve Heard Just What I Seen is a series of three exhibitions that each explore the intersections between visual art and music. Its borrowed title, from Bo Diddley’s 1956 blues classic Who Do You Love? is an apt reference for this final installment which presents the icons, muses, historical moments and figures who inspired musicians and fans alike; eliciting new movements, genres and communities, instigating change on both a personal and global level. As much as music is individually felt, it is also a powerful galvanizing force, bringing people together physically and psychically to celebrate and protest.

Diddley was an inventor, not limited to songwriting but extended to his self-given name and his rectangular guitar, which he designed and manufactured through Gretsch. Perhaps he is best described as a re-negotiator who assessed and tweaked his options, rendering the familiar in ways previously unimaginable. This capacity to harness untapped potential, an extra-sensitivity to sights and sounds, to see, hear or feel what lies beneath, above and in-between, also speaks to the role of the artist. The images and objects the artist makes of what and how she sees the world in turn guide people and cultures towards a deep and complex understanding of themselves.

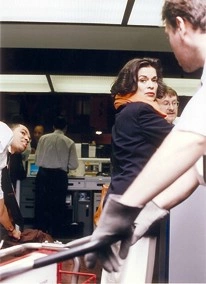

A portrait of the iconic Bianca Jagger hangs on the exhibition’s most forward-facing wall. Bianca Jagger Index Cover (1998), by Wolfgang Tillmans speaks to the creative exchange between romantic partners (with Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones) as well as how Ms. Jagger, as culturally relevant now as ever, was a muse who embodies the shared desire to carve out a personal stake, to define not just a moment but oneself through ingenious personal expression. Like Diddley, Jagger has a knack for performative bravado, leaving rumors and legends in her wake.

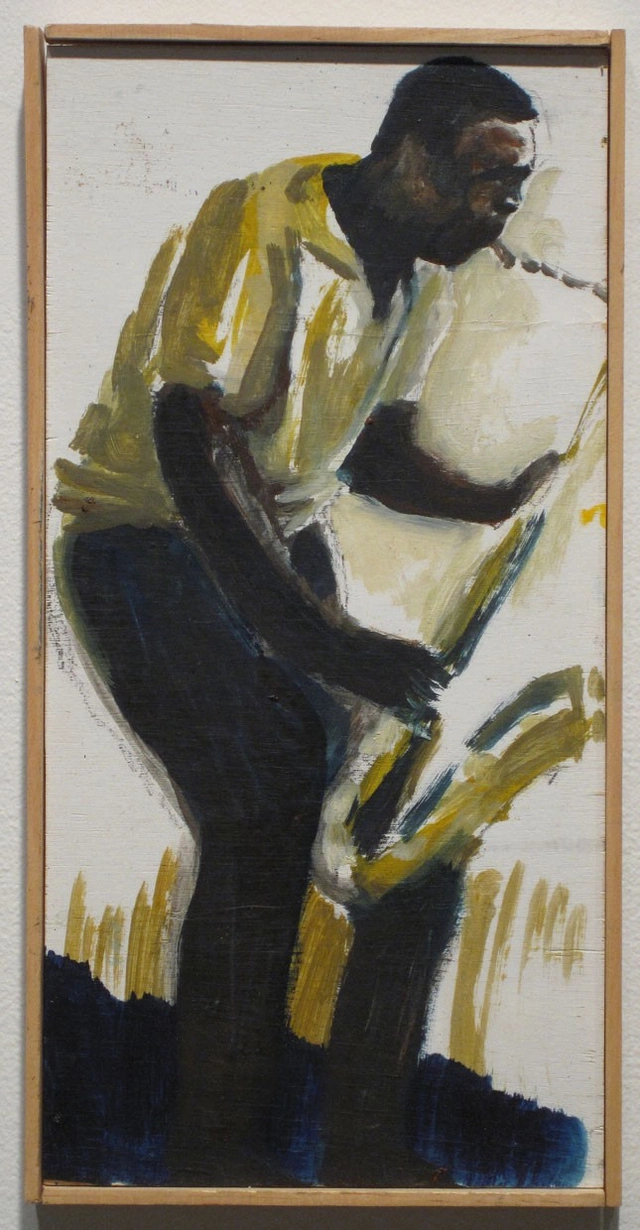

Scott Olson is an abstract painter, a moniker that might connote a tired and overrun genre that apexed half a century ago. And yet, the artist’s small-scale Untitled (2009), of interlocking and disengaging orbs and grids feels new and unencumbered by art history. Untitled is traditionally crafted, and like many of his other works composed with bygone materials like rabbit skin glue and marble dust, which help achieve the exquisite surface. Olson came to painting by way of experimental filmmaking and music; thus, his approach carries a multi-directional, durational and improvisatory tone, while still reliant on technical proficiency and expert knowledge of his tools. Berry van Boekel’s icon-like painting John Coltrane (My Favorite Things) (2009), is one of many musician’s portraits in his oeuvre. Coltrane was also rigorously studied, playing and writing for saxophone through high school and college, working under established musicians and mentors until he struck out on his own, subsequently inventing an entirely new type of music called free jazz.

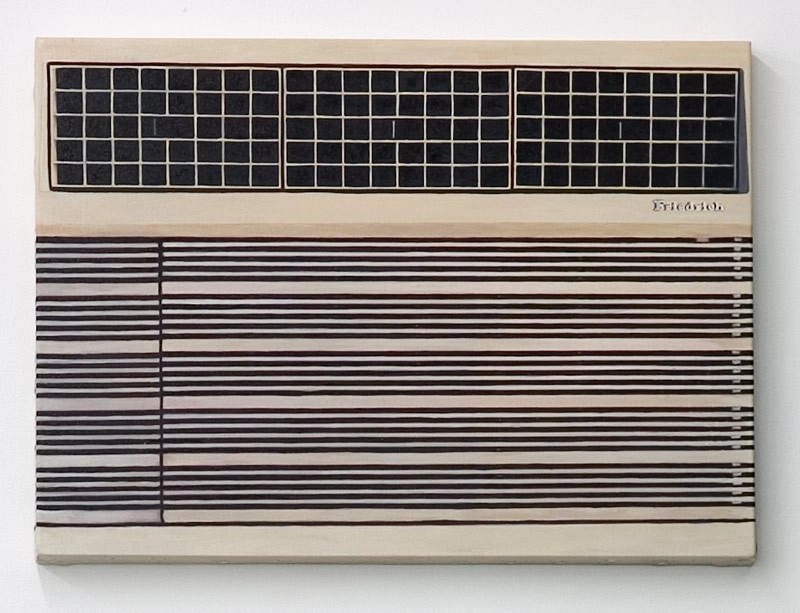

Unlike today’s digital audio files, in Coltrane’s day music was recorded for analog records. Craig Kalpakjian’s An Audio Obstacle Course (Trackability Test Record for Stereo Cartridges) (2011) plays with this outmoded yet fetishized musical object. The artist extended his manipulation of light waves and reflections to an album sleeve, itself the cover for a record used to calibrate and optimize levels, balances and weights of a record player. Kalpakjian’s print of concentric, undulating waves mirrors the invisible waves produced by sound. Noise and waves as sound and music appears again in Adam McEwen’s Commission #2: Friedrich (1) (2005), a trompe l’oeil painting of the front of an air conditioner. While not about music per se, the white noise made by the object McEwen depicted might serve as impetus for sound art, an experimental genre of music composition, performance and installation wherein artists use sound—much like paint, ink, or clay—as material.

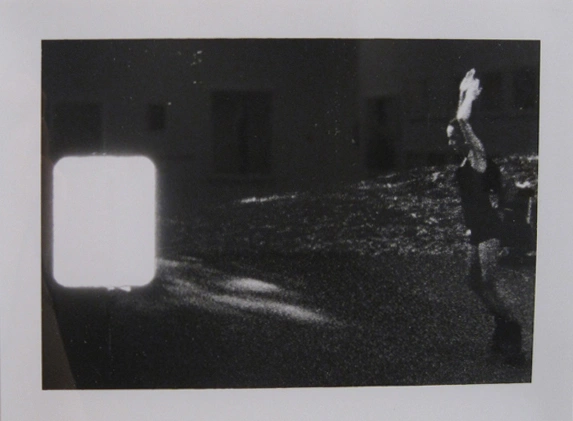

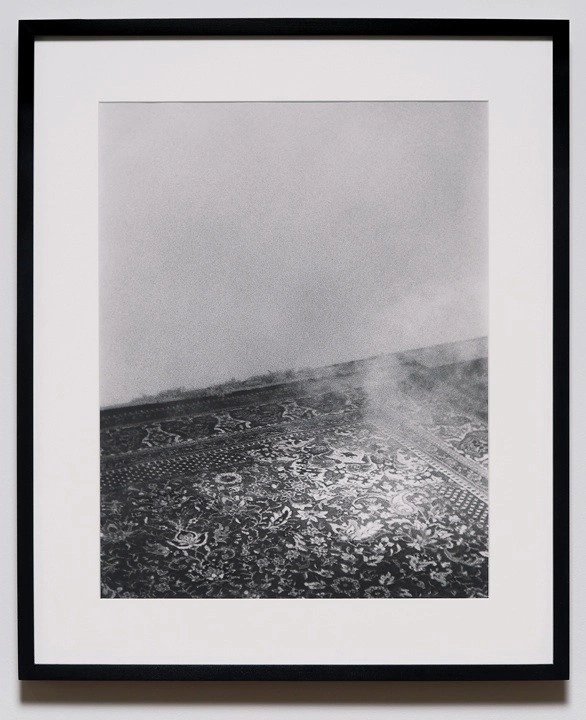

Unafraid to experiment and risk failure, artists are celebrated as much for their work as their daring. Trisha Donnelly’s inexplicable Untitled (2004), seems to touch on that creative energy. A black and white photograph, it depicts a dancer (or perhaps a swimmer) posed in some sort of dive toward a white square. Implied is a jump into the unknown, but it’s a leap into a blinding white light rather than a black void, suggesting the transformation of death, a spirit freed of the body and released into the universe. Similarly oblique is Adam Putnam’s Untitled (Wisp) (2007), a black and white photograph of smoke rising from a Persian carpet. The angle of the shot is low lying and awkward, as though the eye behind the camera wasn’t human but as otherworldly and alchemical as the image. Wisp reads as a metaphor for art making itself, conjuring meaning from the immaterial, seemingly insignificant and fleeting.

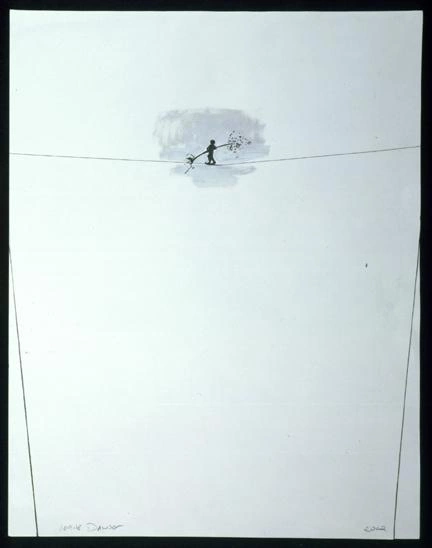

It’s a skillful balancing act that the artist performs, between making work too opaque to communicate or so populist that it loses its potency. As with music, there is always a push and pull between the personal and the universal, a tension that appears here in Verne Dawson’s Tightrope Walker (2002). A tiny figure hovers with a vibrating balancing pole on a thinly drawn line positioned at the top of the paper, an image that communicates a precarious mental state all can relate to. Not apparent in this work is the artist’s often found inspiration in country music, a reference that underpins his more elaborate and fanciful landscape paintings. Rap music and hip hop culture appear in Wardell Milan’s Smooth Girls No. 3 (2008), a collage of a Latina in a suggestive pose, wearing big gold earrings, her body obscured by accordion-folds and intricately cut and combined images of blooming roses. Milan tore pages from the music and style magazine Smooth, which also features a monthly centerfold of a woman of color, juxtaposing and recombining these fragments with antique prints of flowers. The artist locates divergent markers of identity, masculinity and femininity and in bringing them all together, suggests that one can embody and play with gender, sexual and cultural binaries.

Gender confusion, particularly in the form of long hair, appears throughout the exhibition. In the 1960’s men with shaggy long hair were viewed as transgressive and even threatening to the politically and socially conservative majority. Even as late as the 1970’s—to return to Mick Jagger—the Rolling Stones were considered dangerous, liable to incite riots whenever they played live. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s Almost Cut My Hair equates long hair to political resistance, a stance against militarism and the Vietnam War.

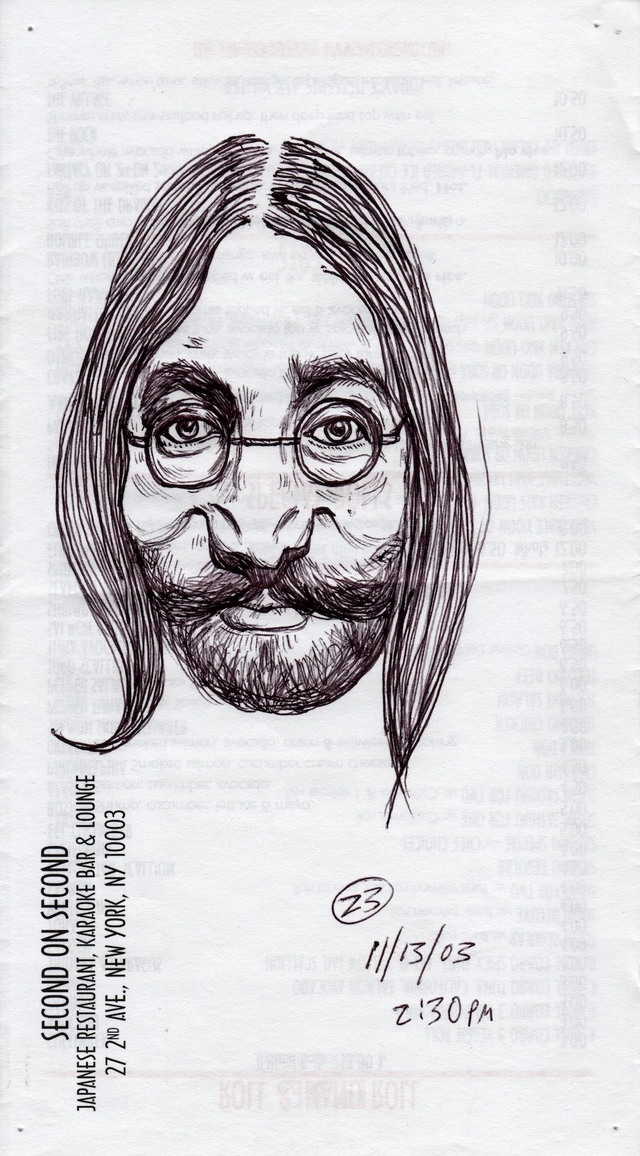

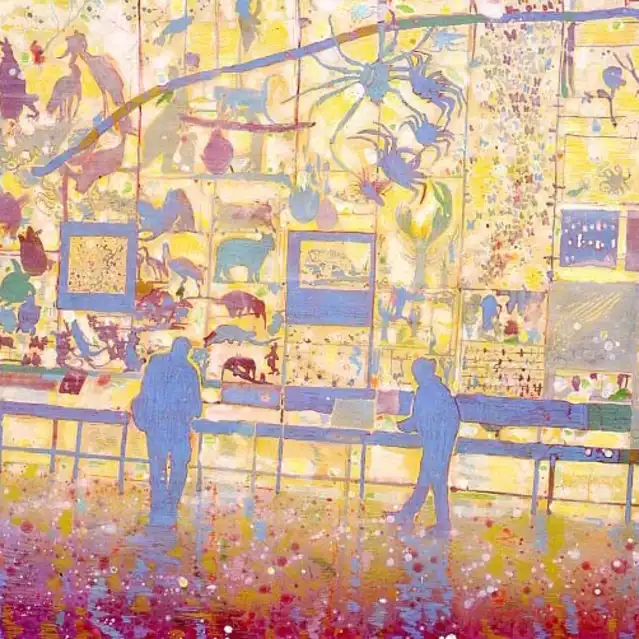

The band’s second gig was famously at the 1969 Woodstock Music & Art Fair, a three-day concert organized to celebrate music and peace. Laura Owen’s Untitled (2004) painting was made across the Woodstock record’s gatefold photo, an image of the 400,000-strong crowd camped out around a standing couple, embracing in a sleeping bag. The Beatles were absent from that weekend, as John Lennon wouldn’t join unless Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band was invited – they were not. Imagine OCD (2:30 PM) by Brian DeGraw is an intimately scaled portrait of John Lennon circa 1969 (round glasses, long hair, beard), executed ad hoc with ballpoint pen on the back of a take out menu. An obvious reference to Imagine, Lennon’s post-Beatles hit about world peace, DeGraw’s title hints at a more personal conflict with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (O.C.D.). This drawing is one of the artist’s many similar Lennon portraits, each accompanied by a time, date and number; in this case, 2:30 PM, 11/13/03, and 23, specifics that mark not only when the artwork was made but perhaps when it had to be made.

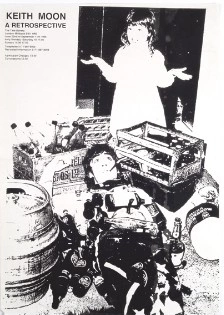

The Who played a very long set on the second day of Woodstock, and the band’s drummer Keith Moon appears in Jeremy Deller’s Keith Moon: A Retrospective (1995). The silkscreen poster seems to advertise an exhibition of Keith Moon held at the Tate, London; however, it’s a spoof, like many of Deller’s artworks that explore cultural history and artifacts. Moon was as famous for his innovative zig-zag drumming as he was infamous for his hardcore partying, he invented as many strange beats as he did rock star clichés (like trashing a hotel room). Perhaps Deller’s poster celebrating a legend that drank himself to death suggests a critique of British culture: Moon depicted laid up in the chaos of a destroyed room, a child with their hands in the air as if to say “oh well” hovering behind him.

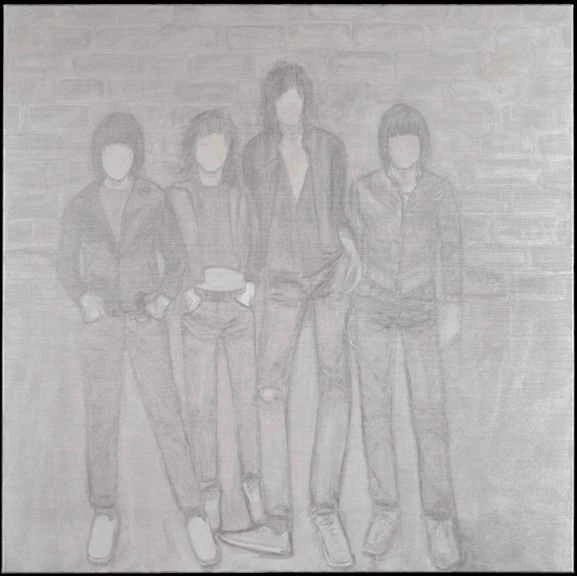

The Velvet Underground were similarly known for their non-music making activities. Famously “discovered” and promoted by Andy Warhol, the band was of the Factory scene and all that came with it. At age seventeen Stephen Shore found his way to the Factory, observing the activity that swarmed around Warhol and the Velvets. Room 219, Holiday Inn, Winter Haven, Florida (1977-2003) was shot after this formative time, during one of Shore’s cross-country trips of the 1970s. The image of a slumberer, prostrate in rumpled sheets with a cheap exotic mural painted on the wall above the bed, connotes a dream or an escape, perhaps from the garishly baroque, depraved room. This image exemplifies Shore’s documentary style, imbued with an emotional strangeness only possible from someone with an intensely observant gaze. The Ramones were another iconic New York City band with a distinct look – long backed bowl cuts, leather jackets and high tops – Brooklyn punk to the Velvets’ Manhattan avant-garde. Silke Otto-Knapp’s Group (Ramones) (2006) rendered in silver, shadowy silhouettes conjures the members by simply outlining their unmistakable figures and garb.

Returning to the present day, Shannon Ebner’s Raw/War (2004) nonetheless calls to mind political issues around which Woodstock was formulated. From the artist’s Dead Democracy Letters series, this black and white photograph of large handmade letters that spell R-A-W, were set up at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, a pre-historic location in the middle of an urban landscape where tar has naturally seeped up from the ground for tens of centuries. The Hollywood sign-like presentation, shrouded by Israeli palm trees and other desert plants, reflects W-A-R on the glossy surface of the tar. The locale isn’t immediately recognizable and suggests a place far more exotic, perhaps Middle Eastern. The work calls to mind our state of perpetual war and controversial engagement with Iraq, which many believe was invaded only to seize control of the region’s crude oil supplies.

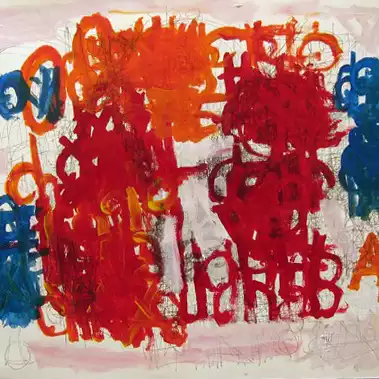

Frances Stark’s large scale paper collage I Went Through My Bin Yet Again (2008), shifts focus back to more personal concerns. Exactly what is meant by the artist’s title is unclear, but within the context of this exhibition the “bin” might reference a storage container for keepsakes, photographs, or records. The scraps of torn paper dangling from the “hand” reflect as much, suggesting either an emptying out of old memories or perhaps an inventory of past events.

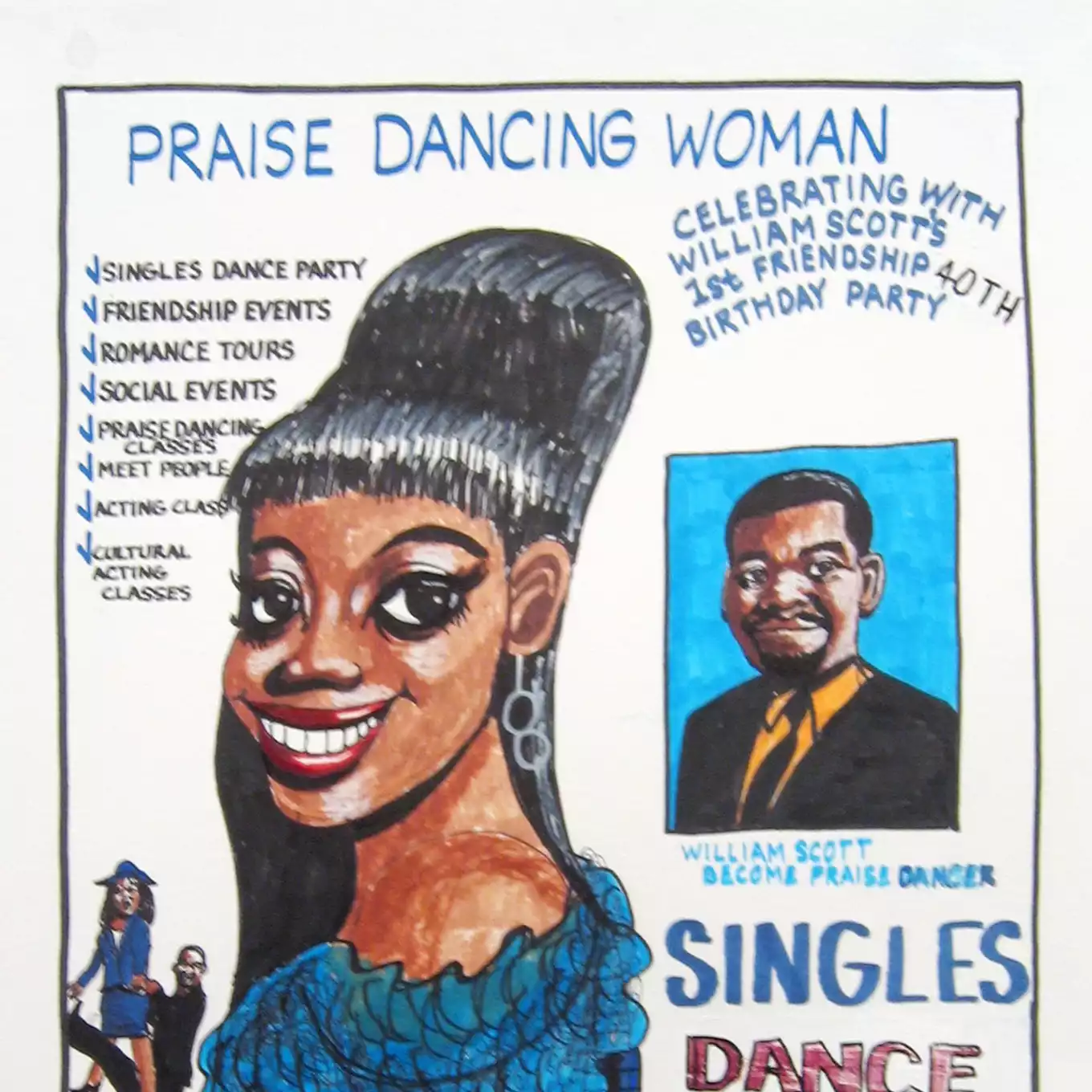

The exhibition closes with a more celebratory feeling, capped off on the most rear-facing wall with William Scott’s Singles Dance Party (c. 2002). Part drawing part flyer, this image of a woman in a blue party dress accompanied by the caption “Praise Dancing Woman,” celebrates and advertises a dance party to be held on July 28th, 2004. Scott’s piece perfectly accompanies Rikrit Tiravanija’s Untitled 1993 (shall we dance) (1993). A multi-part work activated by the viewer, it comprises The King and I soundtrack on an old fashioned record player, casually set up on two chairs. Visitors are encouraged to find a partner to dance with and place the needle on the record. As the Eisenberg Family Gallery is adjacent to Riverview School’s social spaces, I hope students and faculty will come together and experience the music, available for all to play and enjoy.